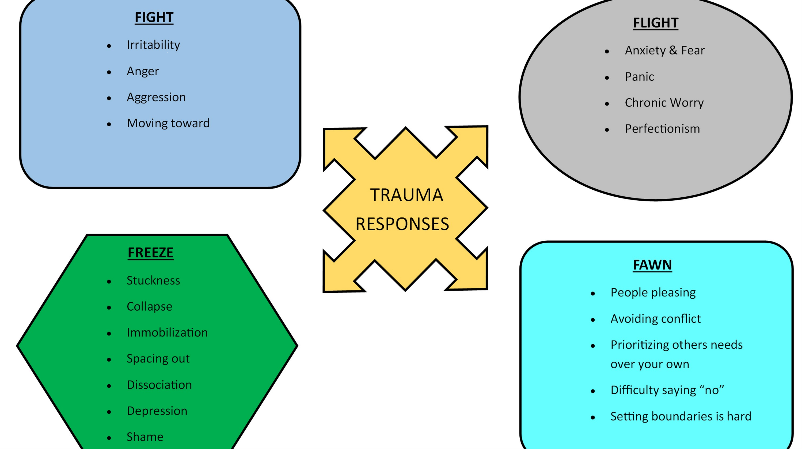

When our body feels unsafe, our brain takes automatic steps to protect us. That reaction can vary from person to person, from time to time. Most of us have heard of the fight or flight response. Our adrenaline forces us to run from danger or fight against it, a natural survival tactic. However, these are not the only survival responses our brain offers in the face of danger. Very often, we can also experience a freeze response, much like a deer in headlights. We can freeze, unable to speak, or fight back when we feel unsafe. This response isn’t due to being unprepared for fighting. Just like a deer could often run out of the way of a car coming towards it but they don’t because their brain is focusing all it’s energy on preparing the body for contact. Another survival response includes fawning, which can look like going along with a dangerous situation due to the threat of greater danger if we fight back. We can’t predict the way our brain might react, we can’t control those survival mode behaviors. Our brain takes control, leaving behind the voluntary thoughts and actions.

Understanding and accepting these involuntary responses can be challenging to a survivor of assault or abuse. Many might ask them, “Why didn’t you fight back??” “Why didn’t you try to run??” and the survivor may know, “I could never have fought them off” or “I could have gotten killed if I had done anything differently” but much more often, that survivor is thinking the same questions because we all think we would react a certain way if we were in that situation. Shame may overpower rationality and induce depression and trouble identifying healthy boundaries. But our brain does the best it can to help us survive in these situations, and in turn survivors have done the best they could when they weren’t safe.

Understanding and accepting these involuntary responses can be challenging to a survivor of assault or abuse. Many might ask them, “Why didn’t you fight back??” “Why didn’t you try to run??” and the survivor may know, “I could never have fought them off” or “I could have gotten killed if I had done anything differently” but much more often, that survivor is thinking the same questions because we all think we would react a certain way if we were in that situation. Shame may overpower rationality and induce depression and trouble identifying healthy boundaries. But our brain does the best it can to help us survive in these situations, and in turn survivors have done the best they could when they weren’t safe.

Many survivors have trouble grasping their assault because they did not respond the way they thought they would. Sometimes this looks like a survivor who didn’t say “No” but they are still experiencing the trauma because they did not feel safe in the situation they were in. The absence of a “No” is not a “Yes.” If we aren’t leaving space for someone to say no, if we aren’t making sure they feel safe enough to set their boundaries, if we don’t give them equal control in the situation, then how do we know they feel safe in the encounter. Fawning can complicate sexual assault because while the perpetrator may not have realized the survivor felt unsafe, the survivor has still experienced the physiological trauma response. That trauma will still linger and they can still experience lasting effects of a sexual assault.

The automatic response from our brain in a traumatic situation can have lingering effects. Surviving trauma is not the end for our brain. Our brain can become more sensitive to threats after experiencing trauma, sometimes sensing threats when none is present. The alarm system in our brain may go off when we’re overstimulated or are reminded of the traumatic moment. In those moments, the chemicals that activate our survival mode are released and we may go into fight or flight, or we might freeze or fawn, even with no danger in sight. If our brain develops these responses often enough, these responses can seep into our regular responses. This can look like people pleasing, workaholic tendencies, aggression, dissociation, etc. This can affect the way we interact in our relationships, the ways we respond to conflict, the way we think of ourselves internally. Trauma lingers in our bodies, sometimes long after we have escaped that situation.

Providing education about trauma responses helps survivors by giving context to their actions. Psycho-education is provided to survivors by our advocates and therapists while providing emotional support and validation to support that survivor. While many people find relief from anxiety and depression medications, working through trauma with a therapist can actually resolve the symptoms by getting to the root of the trauma and reprocessing memories. Identifying triggers, developing healthy coping skills, examining our behaviors, and reprocessing helps survivors get rid of trauma stored in the body, which will help our body feel safe and prevent trauma responses when they are not necessary.

No matter what response a survivor had during their trauma, we believe them and want to provide support. All experiences are valid and our advocates provide a safe space to talk on our 24 hour hotline. Advocates can also provide therapy referrals to our free trauma therapists at Hope and Healing or provide information on other mental health services. We hope you know you are not alone.